The pioneer of the body shot KO, 'Ruby Rob' Fitzsimmons, and the fistic legacy he left behind

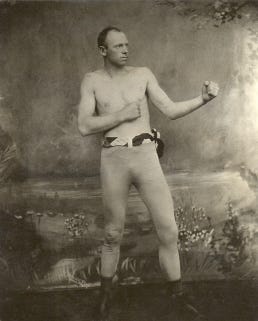

The smallest man to ever hold the heavyweight title learned how a well-placed punch to the body could be a great equalizer among men.

You talk about some of the best or weirdest or just most interesting ways to win a fight, it’s not going to take long before someone brings us the murky phenomenon of the body shot KO. It mystifies and enthralls us. How could it not? A fighter, still perfectly conscious and in possession of all (or at least most) of his wits, takes a perfect blow somewhere in the neighborhood of the belly region, which often appears at first to affect him not at all. But then something bad happens. The body registers the damage, sends an urgent message radiating outward. Soon comes total system failure, full shutdown, and a look of utter agony twists across the face.

In MMA circles, Bas Rutten is often considered the father of the brutal body shot finish. He made a living off the “liver shot” left hook in Pancrase, and then somewhat accidentally turned it into his catchphrase with his workout tapes and CDs, which were in damn near every MMA gym in America circa 2004-05. In PRIDE, Mirko “Cro Cop” Filipovic punished many a tum-tum with his sickening body kicks. In the UFC, David “The Crow” Loiseau introduced fans to the power of a spinning back kick to guts when he famously used it to finish “Chainsaw” Charles McCarthy at UFC 53 in 2005.

But if you want to talk about a real pioneer of the body shot? Who just happens to have one of those strange and fascinating life stories that are so plentiful in fight sports history? Then you’ve got to go all the way back to “Ruby Rob,” aka “The Freckled Wonder,” aka the fighting blacksmith himself, Robert James Fitzsimmons.

These days, Bob Fitzsimmons is mostly remembered for two things: 1) He was boxing’s first three-division champ, having won first the middleweight title, then the heavyweight title (despite only weighing about 165 pounds), and finally the light heavyweight title (which he won at the age of 40); 2) He is often said to have coined the phrase “the bigger they are, the harder they fall,” which was his way of saying that he had no problem giving up 40 or 50 pounds when he took on the heavyweights of his day.

Fitzsimmons was born in Cornwall, England, in 1863, the youngest of twelve (12!!) children. His father was Irish, his mother (whose maiden name, awesomely, was Jane Strongman) was Cornish, but when Bob was still a young boy the family moved to New Zealand, where his father set up a blacksmith shop in the port city of Timaru. That’s where Fitzsimmons did most of his growing up, swinging a sledge in his father’s forge and occasionally fighting drunk or otherwise unruly patrons. It was even later suggested that this helped business, as supposedly some people would simply hang around the blacksmith’s waiting for someone to show up and get handled by the blacksmith’s gangly teenage son.

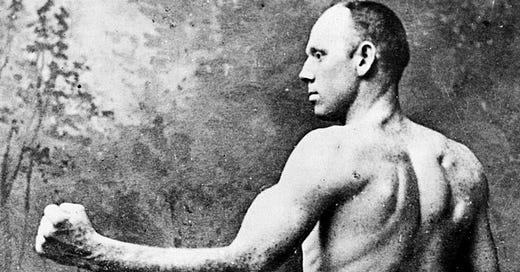

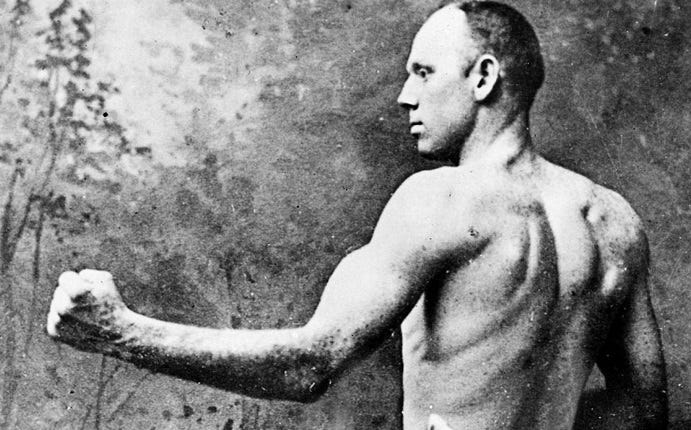

In his book, “The Heavyweight Champions,” John Durant writes that Fitzsimmons “probably never knew what the inside of a school looked like.” He stood around six feet tall, with long arms and skinny legs. He was sometimes said to have been built like a heavyweight only from the waist up. His shock of red hair earned him the nickname “Ruby Rob,” and it somehow stuck even after he went mostly bald in his late twenties.

The story goes that Fitzsimmons’ life changed forever when the great bareknuckle champion Jem Mace visited New Zealand to put on a sort of boxing clinic that culminated with a tournament for amateur heavyweights in the region. Fitzsimmons was in his late teens at the time and is said to have weighed only about 140 pounds. Mace told him he was more of a lightweight than a heavyweight and advised him to sit the tournament out. Fitzsimmons insisted on fighting, and ended up winning the whole thing, to Mace’s delighted astonishment.

News of that tournament victory spread, and soon Fitzsimmons had himself an actual boxing career. After taking it as far as he could in New Zealand and Australia, he headed for California, where, in 1890, the heart of west coast pugilism was undoubtedly the boom town of San Francisco.

“He had a hard time getting it at first, for no one ever looked less like a fighter and his name was unknown in California,” Durant writes. “He was now bald except for a vivid fringe of red hair above his ears and his head and torso were covered with freckles. He had a small head, narrow eyes, and he seemed to be all legs. ‘A knock-kneed crane,’ ‘a bald-headed kangaroo,’ were some of the things they called him. Good-natured Bob, who was liked by everyone, did not care what he was called as long as he could get a chance to prove himself in the ring.”

The more chances Fitzsimmons got to fight, the more of a name he made for himself. He wasn’t big or even all that quick, but he had amazing recuperative abilities after being hurt and was one of the most powerful punchers of his day. That had tragic consequences at Jacob’s Opera House in Syracuse, New York, when Fitzsimmons knocked out Con Riordan in a gloved exhibition. Riordan never regained consciousness and died shortly after. Fitzsimmons was later charged with manslaughter, but it didn’t stick.

Still weighing just 150 pounds, Fitzsimmons fought “Nonpareil” Jack Dempsey for the middleweight title in 1891. Fitzsimmons reportedly put such a bad beating on Dempsey that he begged both Dempsey and his corner to call the fight off. Finally, after knocking Dempsey down at least a dozen times, Fitzsimmons succeeded in knocking him all the way out. Then he picked him up and helped carry Dempsey to his corner.

As Fitzsimmons eyed bigger game at heavyweight, he began to focus on the body shot as a great equalizer among men. The bigger, stronger guys at heavyweight might be able to take more of what Fitzsimmons could dish out when it came to head shots, but he found that a well-placed blow to the body would hurt anybody, no matter how big they were. (He wasn’t the first fighter to learn this lesson; the English bare-knuckler Jack Broughton used to call his specialty belly punch “The Projectile.”) As a heavyweight, Fitzsimmons increasingly incorporated it as part of his overall attack as a way of evening out the odds against much bigger opponents.

This famously cost him in an 1896 bout against Tom Sharkey in San Francisco. The fight was put on by the San Francisco Athletic Club, which hired famed lawman Wyatt Earp as a referee. Earp made a big deal out of entering the ring armed with his Colt pistol and only reluctantly agreed to give it up during the bout, the result of which was to give him the attention he apparently craved. Earp further inserted himself into the bout when Fitzsimmons crumpled Sharkey with a body shot, which Earp ruled a low blow over objections from many in the crowd who insisted it was a legal punch. Sharkey was declared the winner, and Fitzsimmons boiled with rage at Earp, who he would later come to regard as a sort of nemesis.

The good news was that all the press over the incident helped bring attention to Fitzsimmons as a legit challenger for the heavyweight title held by “Gentleman” Jim Corbett, who’d won it by knocking out the famed John L. Sullivan in the first gloved heavyweight title fight in 1892. Corbett was known as a scientific fighter and the best of the heavyweights at the time, but he never achieved anything close to Sullivan’s fame. By 1896, he had begun to seem somewhat disinterested with his status as heavyweight champ, fighting rarely and using various exhibitions, theatrical appearances, and even a bout done exclusively for Thomas Edison’s kinetoscope parlors, to make his living.

Fans soon tired of this, and they let Corbett know it. They wanted to see him face a real challenge. When he made public appearances, Corbett found himself pelted with the same question that gradually became an accusation: When are you going to fight Fitzsimmons? Finally Corbett gave in, and the heavyweight title fight was set for an outdoor stadium in Carson City, Nevada, on St. Patrick’s Day, 1897.

The bout was one of those late-century wonders that seemed loaded down with historical firsts. It was the first time an arena was built specifically for a title fight (though this would become a financially reckless trend soon enough). It was also the first title fight filmed live on location as a moving picture. And, among Fitzsimmons’ team, the first time a woman appeared in a fighter’s corner – the first of his Fitzsimmons’ four wives.

Depending on the source, Fitzsimmons weighed somewhere between 156 and 165 pounds for the fight. Corbett had never been a huge heavyweight himself, but he still seemed significantly bigger than the middleweight Fitzsimmons. Early on in the fight, it seemed like the champion was in no danger whatsoever. He jabbed Fitzsimmons at will, stayed largely out of range himself, and returned to his corner after the fourth round bragging that he hadn’t “felt a single punch” of Fitzsimmons’ so far. In the sixth, Corbett dropped a bloodied and battered Fitzsimmons, who took until the count of nine to make it back to his feet.

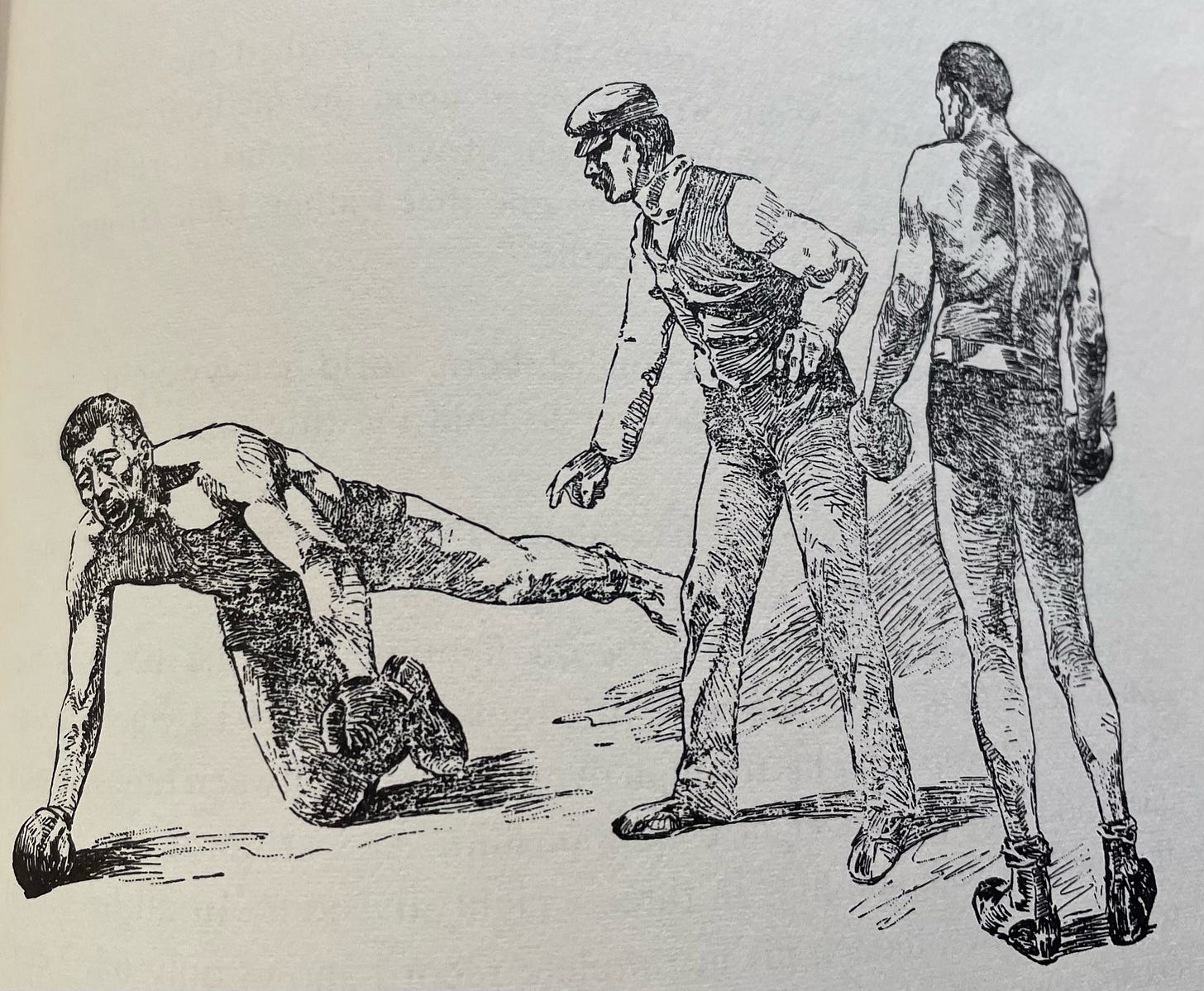

But once again, Fitzsimmons’ amazing durability and gift of recovery saved him. He battled his way back into the fight, surprising Corbett with his resiliency, and in Round 14 hammered Corbett to the body with a short left hand that dropped the champion.

The punch itself is difficult to make out in the grainy film of the fight. What’s more clear when watching it is Corbett struggling to rise, crawling on his knees toward the ropes, reaching out for something he could use to haul himself back to his feet. You can almost feel his pained confusion in that moment. He was still totally with it, still very willing to fight, but his body simply wouldn’t do it. He’d been struck by that some system failure we’re used to seeing in the fighters of today when a body shot takes its toll. Corbett simply couldn’t understand it, nor could he accept it, even as he heard the referee counting 10 and calling the fight for Fitzsimmons.

According to some ringside reports, Corbett stayed down until he’d recovered enough for his body to obey him again, then he immediately rushed at the celebrating Fitzsimmons and tried to continue the fight. Others say the scene was less dramatic, but that a weeping Corbett had to be practically pulled out of the ring and dragged to his locker room. Afterwards, he is said to have kept repeating the same sentence over and over: “It was a lucky punch.”

In an account of the fight, a newspaper reporter quoted a doctor he’d spoken with who referred to it as a punch to the “solar plexus.” This is said to be how the term for that part of the human midsection first entered popular usage.

The new champion Fitzsimmons initially declared himself done with boxing now that he’d reached its zenith. “I am now prepared to enter some other occupation,” he said. “I will never fight again.”

That, of course, proved to be a pretty typical combat sports retirement. He kept fighting until the age of 52, and even participated in some wrestling matches of questionable authenticity. He lost the heavyweight title to James J. Jeffries in 1899, then later joined Jeffries in his cross-country exhibition tour, where Fitzsimmons made headlines by starching his own manager with a one-punch knockout in the lobby of a hotel in Butte, Montana, in 1902. Apparently, Fitzsimmons didn’t like the speed with which the manager, Clark Ball, had gone off to try to sign one of Jeffries’ local opponents on this tour. When he confronted Ball about it, Ball resigned as Fitzsimmons’ manager.

“Ball spoke to Fitz in the hotel lobby and asked him to decide what was due him as a manager for past services,” a local Butte newspaper reported. “Fitz replied that he owed Ball nothing. The latter made a hot retort and the Cornishman’s fist shot out like a piston rod on a fast express.”

Even then, Fitzsimmons could still hit. His last fight came in 1914, and he died of pneumonia three years later. He fought well over 100 professional bouts, not counting exhibitions, amateur tournaments, or disagreements with managers and/or customers at his father’s shop. At the end, one of the things he was said to be most proud of was how unscarred his face was despite a lifetime of fighting. That, and his ability to lay any man low with one punch to the gut.