The saga of 'Young' Stribling: The schoolboy fighter who rarely went to school

He fought more than 70 pro bouts while still in high school, became a national celebrity, and *almost* fulfilled his father's dream of becoming a major champion before being cut down in his prime

You want to talk about short title reigns? Then how about this: For a couple hours one night in 1923, W.L. “Young” Stribling was the world light heavyweight champion. Then the referee who’d worked his title bout with champion Mike McTigue got far enough way from the crowd that had gathered that night in Columbus, Georgia, so that he no longer feared being torn to pieces by an angry mob, and then it all got taken away.

Turns out, the 18-year-old fighter hadn’t won the championship after all. The fight – a lackluster affair with little in the way of meaningful action – was a draw. That’s exactly what referee Harry Ertle had called it initially, before the angry crowd had surrounded the ring, refusing to let him leave until he reconsidered. It was only to escape the mob that he called it for Stribling, a high school student from Macon who was then one of the biggest sports stars to ever come out of the state of Georgia. Only after the police had escorted Ertle to safety did the referee correct his decision, and the title stayed with McTigue.

By the time the story found its way into the major American newspapers, the term “fiasco” was being thrown around pretty liberally. None of us this was Stribling’s fault, mind you. Not that it mattered. By all accounts, the kid from Macon was a polite, humble, effortlessly charismatic guy. The fact that he had over 50 professional fights before he turned 18 was as much a testament to his father’s ambition as his own.

The story of “Young” Stribling’s career is one of boxing’s most strangely fascinating but somehow not widely known tales. He was born into a vaudeville stage family in 1904, and became a part of the act almost as soon as he was old enough to walk. He spent his early childhood touring America with his mother, father, and younger brother Herbert, living on the road and getting his homeschooled education between shows.

The family was billed as the “Four Novelty Grahams,” a kind of variety act that usually ended with a semi-scripted boxing match between the two young boys, which the younger Herbert always won for the sake of comedic effect. Though the ending of the bout was fixed, Herbert would later say that whenever he was mad at his brother he saved that fury for their fights, since he knew W.L. would have to let him have a few free shots at some point.

The family’s stage prospects began to wind down by the time America entered World War I in 1917, so the Striblings finally put down roots in Macon, Georgia. Here the boys were enrolled in school for the first time, and the affable W.L. soon became one of the most popular kids in town. His father’s goals for him had never changed, however. From the time he was a toddler, W.L. had been told that it was his destiny to become the world heavyweight champion. This was what his father had wanted for himself in his youth, but he was too small to seriously pursue a career a ring. Thus did his dream get transferred to his sons, who both became pro fighters. They may not have had the term “stage parent” back then, but the family patriarch Willie Stribling was practically the prototype for it.

The good news was that W.L. was a talented athlete. He led his high school team to a state championship, and was generally regarded as one of the best high school basketball players in the nation. “Strib,” as he was known to his friends, loved basketball. But his father never let him forget that his main focus in life should be boxing. He was fighting professionally at 16, traveling all over the south and usually fighting two or three times a month. He missed so much school that it became first a local controversy, and then, as he garnered more fame, a national one. The fact that he was so young, still in high school, and yet fighting grown men for money, that was a big part of his selling point as a fighter. He fought over 70 pro bouts while still in school, and yet the school part was clearly no more than a side gig, if that. It got to the point that a newspaper writer once dubbed him, “the Georgia schoolboy who never goes to school.”

Stribling won a lot of regional titles in those years – he was champion of Georgia, and champion of “the south” in weight classes ranging from featherweight to middleweight – but never a major one. His father still desperately wanted him to become world heavyweight champion, but Stribling didn’t always fare well when he went up in weight – or when he left the south.

In New York City, then the world capital of boxing, the reception was often chilly, in large part because northerners seemed ready to associate him with the white supremacist violence that was raging through the Jim Crow south. Once, at an appearance in Madison Square Garden, Stribling was introduced only to be met with chants of “Ku Klux Clan!”

His fought in several notable bouts in New York, including one for the light heavyweight title in Yankee Stadium, but he typically came up short. The big city writers began calling him “The King of the Canebrakes.” It’s one of those fighting nicknames that sounds complimentary at first, until you realize it’s meant to convey that he was only a champion when he fought the lesser competition of the rural south, where the thickets of canebrakes grew.

Still, Stribling remained good copy for a lot of newspaper writers in America. In Jaclyn Weldon White’s excellent biography, “The Greatest Champion That Never Was,” she recounts how Stribling and his family met and charmed humorist Will Rogers on a cross-country train trip, resulting in a lot of positive press. He was a young, good-looking kid who came off as a polite, God-fearing, wholesome boy. He married his high school sweetheart, stayed out of trouble, and mostly presented the clean cut image of the gentleman prize fighter. In post-war America, people ate it up.

One of the ironies is that, as well-behaved as he was outside the ring, Stribling developed a minor reputation for bending a rule or two inside of it. He was accused of participating in several fixed fights – Stribling and Leo Diebel were both arrested and accused of putting on a sham fight in Omaha in 1927 – and was disqualified a couple times for fouls like hitting below the belt. His reputation for occasional dirty tactics was well-known enough that one newspaper writer advised him against going to fight in England, “where the rules of boxing are actually enforced.” Stribling went anyway, and traded disqualification losses in back-to-back fights against Primo Carnera, who was himself frequently accused of taking part in fixed fights.

Stribling even brushed up against major organized crime figures when Al Capone supposedly wined and dined his parents in the hopes of taking over a controlling interest in the young fighter just before he fought eventual heavyweight champ Jack Sharkey in 1929. “Pa” and “Ma” Stribling were polite, but ultimately refused the offer, they said.

One of the most interesting and bizarre chapters in Stribling’s non-fighting life was when he, along with much of the rest of the country, became fascinated by air travel. By the late 1920s and early ‘30s, flight schools had begun to pop up all over the nation. A lot of people told themselves that, the same way automobiles had taken over to become a fact of everyday life for most Americans, soon almost everyone would have their own planes to zip around in. Stribling learned to fly and used some of his boxing money to buy his own plane. Soon he was enmeshed in the local pilot community.

A reminder of the risks involved came in 1928, when the flight school Stribling attended set out to promote an air derby that had come to town. Samuel “Buck” Steele, along with one passenger, flew over downtown Macon to drop flyers advertising the air derby. To help draw attention to the skies, they also tossed lit firecrackers from the plane. One of those firecrackers exploded beside the plane’s wing, disabling it and sending the plane rocketing into the sidewalk outside a downtown pharmacy. The two men in the plane were killed instantly, along with a bystander who was struck by the falling plane. A crowd rushed to the crash site, but their weight on the smashed sidewalk caused it to collapse, injuring 12 more people.

Incredibly, the air derby continued as scheduled anyway, but the disaster led to the closure of the local flight school. Far from being deterred, Stribling decided the time was right for him to step up and fill the gap in the flying community. Soon after the crash he applied for and was granted permission from the city council to open his own flight training academy – the Stribling Aerial School.

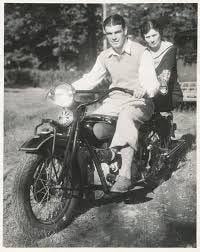

You might not be surprised to learn that the boxer who fought nearly 300 pro bouts and was an early adopter of recreational air travel died young, but it wasn’t either of those two dangerous pastimes that caused it. Instead it was a motorcycle accident in 1933, when Stribling was only 28 years old. He was home in Macon, headed to the hospital to visit his wife and their newborn baby. He waved to a friend in a passing car and didn’t see another car coming up behind it, moving into the oncoming lane to pass as Stribling’s friend slowed to greet him. Stribling collided with the car and went flying through the air. When his friend rushed to his side, Stribling lay in the street with his foot almost entirely severed from his leg.

“Well kid,” he’s said to have told the friend, “I guess this means no more roadwork.”

Two days later, Stribling died of his injuries in the same hospital he’d been headed to visit. It was a shock to the boxing world, but especially to the people of Macon, where Stribling was a beloved local celebrity. Many of them had eagerly followed his career since he was a teenager, holding him up as a source of local pride. Then, just like that, he was gone.

In a lot of ways, his was the kind of fame and the kind of career that was indicative of the times. Because of his youth, his charm, and through no small part because of his father’s savvy and relentless drive for constant publicity, Stribling became a sort of viral sensation of his day. “Pa” Stribling never missed a chance to monetize his son’s fame, and was even one of the first people in the American sports scene to truly capitalize on the potential for endorsements. He also funneled the money his son earned in the ring into multiple investments for himself, including some real estate ventures that took a major hit during the Great Depression. He never let his son waver from the goal of becoming a major boxing champion, even when that meant forcefully guiding him back to the ring and away from pursuits that Stribling might have enjoyed more, like basketball.

He may never have become a major champion, but his short, eventful life still makes for an incredible story, even almost a century later.